Understanding Class Based Weighted Fair Queuing on ATM

Available Languages

Contents

Introduction

This document provides an introduction to traffic queuing using class-based weighted fair queuing (CBWFQ) technology.

Weighted fair queuing (WFQ) enables slow-speed links, such as serial links, to provide fair treatment for all types of traffic. It classifies the traffic into different flows (also known as conversations) based on layer three and layer four information, such as IP addresses and TCP ports. It does this without requiring you to define access lists. This means that low-bandwidth traffic effectively has priority over high-bandwidth traffic because high-bandwidth traffic shares the transmission media in proportion to its assigned weight. However, WFQ has certain limitations:

-

It is not scalable if the flow amount increases considerably.

-

Native WFQ is not available on high-speed interfaces such as ATM interfaces.

CBWFQ provides a solution to these limitations. Unlike standard WFQ, CBWFQ allows you to define traffic classes and apply parameters, such as bandwidth and queue-limits, to these classes. The bandwidth you assign to a class is used to calculate the "weight" of that class. The weight of each packet that matches the class criteria is also calculated from this. WFQ is applied to the classes (which can include several flows) rather than the flows themselves.

For more information on configuring CBWFQ, click on the following links:

Per-VC Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing (Per-VC CBWFQ) on Cisco 7200, 3600, and 2600 Routers.

Per-VC Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing on RSP-based Platforms.

Before You Begin

Conventions

For more information on document conventions, see the Cisco Technical Tips Conventions.

Prerequisites

There are no specific prerequisites for this document.

Components Used

This document is not restricted to specific software and hardware versions.

The information presented in this document was created from devices in a specific lab environment. All of the devices used in this document started with a cleared (default) configuration. If you are working in a live network, ensure that you understand the potential impact of any command before using it.

Network Diagram

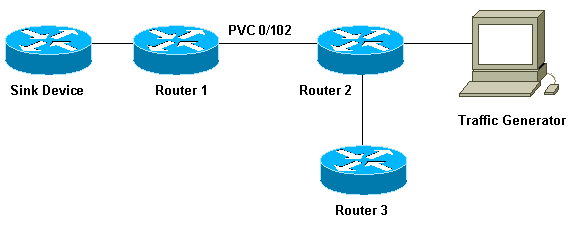

In order to illustrate how WFQ works, let's use the following setup:

In the setup we are using here, packets can be stored in one of the following two queues:

-

The hardware first in first out (FIFO) queue on the port adapter and network module.

-

The queue in the Cisco IOS® Software (on the router input/output [I/O] memory) where Quality of Service (QoS) features such as CBWFQ can be applied.

The FIFO queue on the port adapter stores the packets before they are segmented into cells for transmission. When this queue is full, the port adapter or network module signals to the IOS software that the queue is congested. This mechanism is called back-pressure. On receiving this signal, the router stops sending packets to the interface FIFO queue and stores the packets in the IOS software until the queue is uncongested again. When the packets are stored in IOS, the system can apply QoS features such as CBWFQ.

Setting the Transmit Ring Limit

One problem with this queuing mechanism is that, the bigger the FIFO queue on the interface, the longer the delay before packets at the end of this queue can be transmitted. This can cause severe performance problems for delay-sensitive traffic such as voice traffic.

The permanent virtual circuit (PVC) tx-ring-limit command enables you to reduce the size of the FIFO queue.

interface ATMx/y.z point-to-point

ip address a.b.c.d M.M.M.M

PVC A/B

TX-ring-limit

service-policy output test

The limit (x) you can specify here is either a number of packets (for Cisco 2600 and 3600 routers) or quantity of particles (for Cisco 7200 and 7500 routers).

Reducing the size of the transmit ring has two benefits:

-

It reduces the amount of time packets wait in the FIFO queue before being segmented.

-

It accelerates the use of the QoS in the IOS software.

Impact of the Transmit Ring Limit

Let's look at the impact of the transmit ring limit using the setup shown in our network diagram above. We can assume the following:

-

The traffic generator is sending traffic (1500 byte packets) to the sink device, and this traffic is overloading the PVC 0/102 between router1 and router2.

-

Router3 tries to ping router1.

-

CBWFQ is enabled on router 2.

Now let's look at two configurations using different transmit ring limits in order to see the impact this has.

Example A

In this example, we have set the transmit ring to three (TX-ring-limit=3). Here is what we see when we ping router1 from router3.

POUND#ping ip

Target IP address: 6.6.6.6

Repeat count [5]: 100000

Datagram size [100]:

Timeout in seconds [2]:

Extended commands [n]:

Sweep range of sizes [n]:

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 100000, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 6.6.6.6, timeout is 2 seconds:

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!![snip]

Success rate is 98 percent (604/613), round-trip min/avg/max = 164/190/232 ms

Example B

In this example, we have set the transmit ring to 40 (TX-ring-limit=40). Here is what we see when we use the same ping as in Example A:

POUND#ping ip

Target IP address: 6.6.6.6

Repeat count [5]: 10000

Datagram size [100]: 36

Timeout in seconds [2]: 10

Extended commands [n]:

Sweep range of sizes [n]:

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 10000, 36-byte ICMP Echos to 6.6.6.6, timeout is 10 seconds:

!!!!!!!!!!!!.

Success rate is 92 percent (12/13), round-trip min/avg/max = 6028/6350/6488

As you can see here, the bigger the transmit ring limit, the bigger the ping round-trip time (RTT). We can deduce from this that a large transmit ring limit can lead to significant delays in transmission.

How CBWFQ Works

Now that we have seen the impact of the size of the hardware FIFO queue, let's see exactly how CBWFQ works.

Native WFQ assigns a weight to each conversation, and then schedules the transmit time for each packet of the different flows. The weight is a function of the IP precedence of each flow, and the scheduling time depends on the packet size. Click here for more details on WFQ.

CBWFQ assigns a weight to each configured class instead of each flow. This weight is proportional to the bandwidth configured for each class. More precisely, the weight is a function of the interface bandwidth divided by the class bandwidth. Therefore, the bigger the bandwidth parameter, the smaller the weight.

We can calculate the packet scheduling time using the following formula:

scheduling tail_time= queue_tail_time + pktsize * weight

Total Interface Bandwidth Division

Let's look at how the router divides the total interface bandwidth between the different classes. In order to service the classes, the router uses calendar queues. Each of these calendar queues stores packets that have to be transmitted at the same scheduling_tail_time. The router then services these calendar queues one at a time. Let's look at this process:

-

If congestion occurs on the port adapter when a packet arrives on the output interface, this causes queueing in IOS (CBWFQ in this case).

-

The router calculates a scheduling time for this arriving packet and stores it in the calendar queue corresponding to this scheduling time. Only one packet per class can be stored in a particular calendar queue.

-

When it is time to service the calendar queue in which the packet has been stored, the IOS empties this queue and sends the packets to the FIFO queue on the port adapter itself. The size of this FIFO queue is determined by the transmit ring limit described above.

-

If the FIFO queue is too small to fit all the packets being held in the serviced calendar queue, the router reschedules the packets that cannot be stored for the next scheduling time (corresponding to their weight) and places them in the according calendar queue.

-

When all this is done, the port adapter treats the packets in its FIFO queue and sends the cells on the wire and the IOS moves to the next calendar queue.

Thanks to this mechanism, each class statistically receives a part of the interface bandwidth corresponding to the parameters configured for it.

Calendar Queue Mechanism Versus Transmit Ring Size

Let's look at the relationship between the calendar queue mechanism and the transmit ring size. A small transmit ring allows the QoS to start more quickly and reduces latency for the packets waiting to be transmitted (which is important for delay-sensitive traffic such as voice). However, if it is too small, it can cause lower throughput for certain classes. This is because a lot of packets may have to be rescheduled if the transmit ring cannot accommodate them.

There is, unfortunately, no ideal value for the transmit ring size and the only way to find the best value is by experimenting.

Bandwidth Sharing

We can look at the concept of bandwidth sharing using the setup shown in our network diagram, above. The packet generator produces different flows and sends them to the sink device. The total amount of traffic represented by these flows is enough to overload the PVC. We have implemented CBWFQ on Router2. Here is what our configuration looks like:

access-list 101 permit ip host 7.0.0.200 any

access-list 101 permit ip host 7.0.0.201 any

access-list 102 permit ip host 7.0.0.1 any

!

class-map small

match access-group 101

class-map big

match access-group 102

!

policy-map test

policy-map test

small class

bandwidth <x>

big class

bandwidth <y>

interface atm 4/0.102

pvc 0/102

TX-ring-limit 3

service-policy output test

vbr-nrt 64000 64000

In our example, Router2 is a Cisco 7200 router. This is important because the transmit ring limit is expressed in particles, not packets. Packets are queued in the port adapter FIFO queue as soon as a free particle is available, even if more than one particle is needed to store the packet.

What is a Particle?

Instead of allocating one piece of contiguous memory for a buffer, particle buffering allocates dis-contiguous (scattered) pieces of memory, called particles, and then links them together to form one logical packet buffer. This is called a particle buffer. In such a scheme, a packet can then be spread across multiple particles.

In the 7200 router we are using here, the particle size is 512 bytes.

We can verify whether Cisco 7200 routers use particles by using the show buffers command:

router2#show buffers

[snip]

Private particle pools:

FastEthernet0/0 buffers, 512 bytes (total 400, permanent 400):

0 in free list (0 min, 400 max allowed)

400 hits, 0 fallbacks

400 max cache size, 271 in cache

ATM4/0 buffers, 512 bytes (total 400, permanent 400):

0 in free list (0 min, 400 max allowed)

400 hits, 0 fallbacks

400 max cache size, 0 in cache

Test A

The "Small" and "Big" classes we are using for this test are populated in the following way:

-

Small class - we have configured the bandwidth parameters to 32 kbps. This class stores ten packets of 1500 bytes from 7.0.0.200, followed by ten packets of 1500 bytes from 7.0.0.201

-

Big class - we have configured the bandwidth parameter to 16 kbps. This class stores one flow of ten 1500-bytes packets from 7.0.0.1.

The traffic generator sends a burst of traffic destined for the sink device at 100 Mbps to Router2 in the following order:

-

Ten packets from 7.0.0.1.

-

Ten packets from 7.0.0.200.

-

Ten packets from 7.0.0.201.

Verifying the Flow Weight

Let's look at the weight applied to the different flows. To do this, we can use the show queue ATM x/y.z command.

alcazaba#show queue ATM 4/0.102

Interface ATM4/0.102 VC 0/102

Queueing strategy: weighted fair

Total output drops per VC: 0

Output queue: 9/512/64/0 (size/max total/threshold/drops)

Conversations 2/3/16 (active/max active/max total)

Reserved Conversations 2/2 (allocated/max allocated)

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 7/128/0/0/0

Conversation 25, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.201, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 2/256/0/0/0

Conversation 26, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.1, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

When all the packets from 7.0.0.200 have been queued out of the router, we can see the following:

alcazaba#show queue ATM 4/0.102

Interface ATM4/0.102 VC 0/102

Queueing strategy: weighted fair

Total output drops per VC: 0

Output queue: 9/512/64/0 (size/max total/threshold/drops)

Conversations 2/3/16 (active/max active/max total)

Reserved Conversations 2/2 (allocated/max allocated)

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 7/128/0/0/0

Conversation 25, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.201, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 2/256/0/0/0

Conversation 26, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.1, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

As you can see here, the flows from 7.0.0.200 and 7.0.0.201 have the same weight (128). This weight is half the size of the weight assigned to the flow from 7.0.0.1 (256). This corresponds to the fact that our small class bandwidth is twice the size of our big class.

Verifying the Bandwidth Distribution

So how can we verify the bandwidth distribution between the different flows ? The FIFO queueing method is used in each class. Our small class is filled with ten packets from the first flow and ten packets from the second flow. The first flow is removed from the small class at 32 kbps. As soon as they have been sent, the ten packets from the other flow are sent as well. In the meantime, packets from our big class are removed at 16 kbps.

We can see that, since the traffic generator is sending a burst at 100 Mbps, the PVC will be overloaded. However, as there is no traffic on the PVC when the test is started and, since the packets from 7.0.0.1 are the first to reach the router, some packets from 7.0.0.1 will be sent before CBWFQ starts because of congestion (in other words, before the transmit ring is full).

Since the particle size is 512 bytes and the transmit ring size is three particles, we can see that two packets from 7.0.0.1 are sent before congestion occurs. One is immediately sent on the wire and the second is stored in the three particles forming the port adapter FIFO queue.

We can see the debugs below on the sink device (which is simply a router):

Nov 13 12:19:34.216: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:34.428: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 !--- congestion occurs here. Nov 13 12:19:34.640: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:34.856: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:35.068: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:35.280: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:35.496: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:35.708: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:35.920: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:36.136: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:36.348: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:36.560: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:36.776: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:36.988: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:37.200: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:37.416: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:37.628: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:37.840: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:38.056: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:38.268: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:38.480: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:38.696: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:38.908: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:39.136: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:39.348: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:39.560: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:39.776: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:39.988: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:40.200: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 13 12:19:40.416: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4

Since the packet sizes for both flows are the same, based on the scheduling time formula, we should see two packets from our small class being sent for each packet from our big class. This is exactly what we do see in the debugs above.

Test B

For our second test, let's populate the classes in the following way:

-

Small class - we have configured the bandwidth parameter to 32 kbps. Ten packets of 500 bytes from 7.0.0.200 are generated, followed by ten packets of 1500 bytes from 7.0.0.201.

-

Big class - we have configured the bandwidth parameter to 16 kbps. The class stores one flow of 1500 bytes packets coming from 7.0.0.1.

The traffic generator sends a burst of traffic at 100 Mbps to Router2 in the following order:

-

Ten 1500-byte packets from 7.0.0.1.

-

Ten 500-byte packets from 7.0.0.200.

-

Ten 1500 byte packets from 7.0.0.201.

FIFO is configured in each class.

Verifying the Flow Weight

The next step is to verify the weight applied to the classified flows:

alcazaba#show queue ATM 4/0.102

Interface ATM4/0.102 VC 0/102

Queueing strategy: weighted fair

Total output drops per VC: 0

Output queue: 23/512/64/0 (size/max total/threshold/drops)

Conversations 2/3/16 (active/max active/max total)

Reserved Conversations 2/2 (allocated/max allocated)

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 15/128/0/0/0

Conversation 25, linktype: ip, length: 494

source: 7.0.0.200, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 8/256/0/0/0

Conversation 26, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.1, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

alcazaba#show queue ATM 4/0.102

Interface ATM4/0.102 VC 0/102

Queueing strategy: weighted fair

Total output drops per VC: 0

Output queue: 13/512/64/0 (size/max total/threshold/drops)

Conversations 2/3/16 (active/max active/max total)

Reserved Conversations 2/2 (allocated/max allocated)

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 8/128/0/0/0

Conversation 25, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.201, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63, prot: 255

(depth/weight/total drops/no-buffer drops/interleaves) 5/256/0/0/0

Conversation 26, linktype: ip, length: 1494

source: 7.0.0.1, destination: 6.6.6.6, id: 0x0000, ttl: 63,

As you can see in the output above, the flows from 7.0.0.200 and 7.0.0.201 have received the same weight (128). This weight is half the size of the weight assigned to the flow from 7.0.0.1. This corresponds to the fact that small class has a bandwidth twice the size of our big class.

Verifying the Bandwidth Distribution

We can produce the following debugs from the sink device:

Nov 14 06:52:01.761: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:01.973: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 !--- Congestion occurs here. Nov 14 06:52:02.049: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.121: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.193: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.269: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.341: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.413: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.629: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.701: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.773: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.849: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:02.921: IP: s=7.0.0.200 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:03.149: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:03.361: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:03.572: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:03.788: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:04.000: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:04.212: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:04.428: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:04.640: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:04.852: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:05.068: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:05.280: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:05.492: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:05.708: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:05.920: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:06.132: IP: s=7.0.0.201 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:06.348: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4 Nov 14 06:52:06.560: IP: s=7.0.0.1 (FastEthernet0/1), d=6.6.6.6, Len 1482, rcvd 4

In this scenario, the flows in our small class do not have the same packet size. Hence, the packet distribution is not as trivial as for Test A, above.

Scheduling Times

Let's have a closer look at the scheduling times for each packet. The scheduling time for packets is calculated using the following formula:

scheduling tail_time= sub_queue_tail_time + pktsize *

weight

For different packet sizes, the scheduling time uses the following formula:

500 bytes (small class): scheduling tail_time = x + 494 * 128

= x + 63232

1500 bytes (small class): scheduling tail_time = x + 1494 *

128 = x + 191232

1500 bytes (big class): scheduling tail_time = x + 1494 *

256 = x + 382464

From these formulas, we can see that six packets of 500 bytes from our small class are transmitted for each packet of 1500 bytes from our big class (shown in the debug output above).

We can also see that two packets of 1500 bytes from our small class are sent for one packet of 1500 bytes from our big class (shown in the debug output above).

From our tests above, we can conclude the following:

-

The size of the transmit ring (TX-ring-limit) determines how quickly the queueing mechanism starts working. We can see the impact with the increase of the ping RTT when the transmit ring limit increases. Hence, if you implement CBWFQ or Low Latency Queueing [LLQ]), consider reducing the transmit ring limit.

-

CBWFQ allows fair sharing of the interface bandwidth between different classes.

Related Information

- Per-VC Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing (Per-VC CBWFQ) on Cisco 7200, 3600, and 2600 Routers

- Per-VC Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing on RSP-based Platforms

- Understanding Weighted Fair Queuing on ATM

- IP to ATM Class of Service Technology Support

- ATM Technology Support

- Technical Support & Documentation - Cisco Systems

Revision History

| Revision | Publish Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

1.0 |

15-Nov-2007 |

Initial Release |

Feedback

Feedback